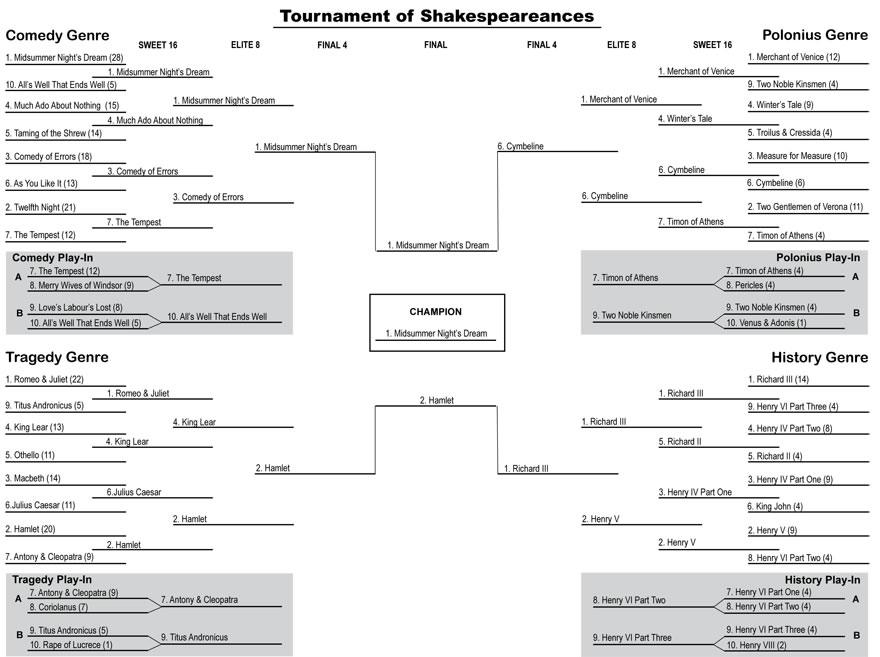

A Tournament of Shakespeareances

Sweet 16: A Top Seed Falls, a 6 Slips Through

For a tournament overview, click here

For the tournament play-in matches, click here

For results of the First Round matches, click here

A number one seed falls, a number six seed plays on, but for the most part, as we get further into the Tournament of Shakespeareances, the more popular plays are proving their merits in stiff competition. Here are the results of the Sweet 16 round to determine the Elite Eight of Shakespeareances.

Comedy Genre

1. A Midsummer Night's Dream (28) vs. 4. Much Ado About Nothing (15)—This is a true showdown for the ages. Dream has been a stage hit since the Restoration, it was one of the first of Shakespeare's plays to achieve Hollywood blockbuster status, and it remains one of his most staged plays. Much Ado About Nothing, a favorite of England's Charles II, inspired a genre of Hollywood comedies and is currently one of Shakespeare's most staged plays. Both score with fast and furious comedy and some memorable playing.

- For Dream, René Thornton Jr. doubling as Theseus and Titania, and Josephine Hall doubling as Hippolyta and Oberon at the American Shakespeare Center (ASC) in 2004.

- For Much Ado, the eavesdropping Benedicks (Alexis Denisof in Joss Whedon's film and Benjamin Curns in the 2012 ASC Actors Renaissance Season) and Beatrices (Amy Acker in Whedon's film, Maggie Siff in the 2013 Theatre for a New Audience production).

- Back to Dream, the hilarious portrayals of Demetrius by Jonathan Minton and Helena by Madeline Wise at Millbrook Playhouse in 2013, two days after a memorable Helena by Emily Whitworth at Synetic.

- Whitworth also makes the highlight reel for Much Ado with her Hero resurrecting in Synetic's staging this year, and Isaiah Ellis nailed a bumbling Claudio at Philadelphia Shakespeare Theatre in 2013.

- Speaking of bumbling, Much Ado has Dogberry, especially John Harrell's incompetent New York police detective with ASC in 2012 and Nathan Fillion's incompetent LA detective in Whedon's Film, along with Alex Perez's self-important security guard portrayal at the Folger in 2009, a portrayal we would see repeated in real life by Metro cops on our way home from the play.

- For every great Dogberry, though, there are a dozen great Bottoms, and Dream delivers its killer blow in Bottom's many deaths: the excited way Brad Lewandowski had members of the audience stab him (Shakespeare Forum, 2012), the varieties of deaths Dean Linnard used for each individual “die” in the script (Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey, 2014), and James Beard dying from a patron's foot odor (ASC 2004).

Dream pulls away from Much Ado thanks to the Rude Mechanicals at Atlanta Shakespeare Tavern in 1997, Shakespeare Theatre Company (STC) in 2012, Synetic in 2013, and Bristol Old Vic/Handspring Puppet Company in 2014. Dream looks hard to beat as it storms into the Elite Eight.

3. The Comedy of Errors (18) vs. 7. The Tempest (12)—Shakespeare would come to write about fairies, witches, magicians, gods, bed tricks, and a statue brought to life, but none of his plays asks us to suspend belief more than The Comedy of Errors. Two identical twins and their identical twin servants, separated as toddlers in a shipwreck, happen to arrive in the same city, dressed in the same clothes, and consequently not only confuse a wife, sister-in-law, close friends, and each other, but also fail to figure out the truth themselves. By all logical reasoning, this play should be finished in 10 minutes. But Shakespeare knew his audience comes to the theater to suspend belief, and that's why Comedy of Errors works so much better on the stage than on paper. While Errors may be Shakespeare's first demonstration of utmost faith in the power of an audience's imagination, The Tempest is his last: a duke and part-time magician was banished 13 years before with his toddler daughter and stranded on a desert island somewhere amid the commercial shipping lanes of the Mediterranean, he learns to command the spirits of the island, create pageants of thin air, and convene his enemies by manufacturing a shipwreck in their imagination. These are such stuff as theater is made on. Successfully staging either play comes down to how much directors believe in Shakespeare's faith. The Tempest is most marvelous when directors stay out of the way of the text (ASC 2011, Taffety Punk 2014), but most productions turn the play into an allegory of colonialism, life, or the retiring Shakespeare himself. Thought-provoking though they may be, they are not always engaging theater. Most productions of Errors, though they may use conceptual settings such as a circus (RSC 1985), South Beach Miami (Alabama Shakespeare Festival, 2000), a cartoon (ASC 2011), London's suburban gangland (National Theatre 2012), or a carnival (Cincinnati Shakespeare Company 2014), rely entirely on Shakespeare's plot devices to carry off the play. As such, The Comedy of Errors can be so engaging, audiences can become as confused as the characters on stage. Thus, it is that Errors emerges from the storm-tossed half of the Comedy Genre bracket to face A Midsummer Night's Dream for a trip to the Final Four.

Tragedy Genre

Colm Feore as King Lear with the blind Gloucester (Scott Wentworth) in the Stratford Festival's production. Photo by David Hou, Stratford Festival.

1. Romeo and Juliet (22) vs. 4. King Lear (13)—This bracket's top seed, Romeo and Juliet (second seed in the whole tournament), needed overtime to get past number-nine Titus Andronicus. Fourth seed King Lear beat out Othello on that match's final shot. Which one is walking on glass here? Lear was famously criticized last year for being “not good. No stakes, not relatable.” Yet, while nobody argues that Romeo and Juliet is a timeless classic that still speaks to today's teens and tweens (and many adults), Julian Fellowes was adamant that Shakespeare's text needed to be updated for Carlo Carlei's 2013 film, and many directors echo Aaron Posner who attempted to “help audiences experience the play as if for the first time” (Folger, 2013) by staging Romeo and Juliet in a variety of specific period settings. I've seen conceptual variations on King Lear (the modern Balkans in the Goodman Theater/STC 2009 staging), but more often the play, when not given a timeless setting, is set with a “once upon a time” aesthete. Furthermore, aside from some interpolations (directors insist on explaining the Fool's disappearance), Shakespeare's text is generally kept intact. The key to a successful Romeo and Juliet is whether we can believe the plot twists of the last two acts: the Friar's scheme to fake Juliet's death, the delayed message to Romeo, and the compressed timeframe. Too many productions fall into these plot holes because of their setting of choice. King Lear starts off in a huge plot hole: Lear's “who loves me most” contest among his three daughters, and his youngest inexplicably refusing to play along. Some productions find ways to make this palatable, but ultimately it doesn't matter. The key to a successful Lear is whether we cry at the end—bonus points for crying at the reunion scene. Colm Feore's Lear leads all scorers in both plays by inducing tears as early as the second act in last year's Stratford Festival production. If the tear ducts stay dry, it's due to bad performances (Anthony Hopkins at the National Theater in 1987), misguided directing (RSC 2011), or poor choices (Chichester Festival at BAM 2014), not the text. With more tears from Lears over the years than satisfaction in Romeo and Juliet stagings, King Lear moves on to the Elite Eight.

2. Hamlet (20) vs. 6. Julius Caesar (11)—With consensus favorite Romeo and Juliet knocked out of the Tournament of Shakespeareances, we now turn to the pundits' favorite, Hamlet. Julius Caesar moved into the Sweet 16 by being the play of today, toppling heavy favorite Macbeth with an incredible run of productions in 2013 that proved the difference between being an underperforming piece of rhetoric and a taut political thriller: ASC Actors' Renaissance Season, RSC's modern African setting, Donmar Warehouse's woman's prison setting. However, when directors don't get it (Folger 2014) or actors don't master it (Maryland Shakespeare Festival 2012), the play dies before even Caesar himself bites the dust. Hamlet, on the other hand, can't help but be a taut political thriller, a taut psychological thriller, and an incisive comedy, all on top of being the world's greatest piece of literature. An onslaught of stellar Hamlets dispatched Antony and Cleopatra in the first round, but in this round we'll see the play's depth. I can think of only one production I didn't like (Atlanta Shakespeare Tavern in 1994), and that was because Hamlet was portrayed as an unmitigated jerk—a valid interpretation. Even the weakest productions I've seen brought something to the play and, subsequently, cast the play's riches in new lights. I had long considered the women to be the play's weakest links, but two productions specifically brought Gertrude and Ophelia to life. The Shakespeare Forum in 2012 emphasized Gertrude's role, as both queen and mother, and Andrus Nichols's performance, especially in the closet scene, floored me as much as any Hamlet ever has. Taffety Punk staged Enter Ophelia, distracted, Kimberly Gilbert's “one-woman” show (but using four actresses) reimagining Hamlet from Ophelia's perspective, through which we see her inevitable slide into disintegration. Playing with such depth, Hamlet here easily dispatches a second Roman tragedy en route to its meeting with King Lear for the Tragedy Genre title.

History Genre

1. Richard III (14) vs. 5. Richard II (4)—When the sampling of productions seen is comparatively small, it can lead to an unfair advantage. That's the case with this battle of the Richards. But the advantage doesn't go to the behemoth Richard III; rather, it's the seldom-seen Richard II that benefits. Of the four stage plays of Richard II I've seen plus the BBC and Hollow Crown versions, only one would I assign anything less than three stars, the 2010 STC version; among the significant reasons that production faltered was the addition of scenes from a non-Shakespearean prequel, Woodstock, at the beginning. The device meant the production focused on being a biography of Richard II instead of focusing on Shakespeare's stagecraft with this play. Despite being all verse, much pageantry, and long speeches, Richard II roils with the tension of a psychological thriller. Two versions at the RSC (1987, directed by Barry Kyle with Jeremy Irons in the title role, 2013 directed by Gregory Doran with David Tennant as Richard) and the BBC version with Derek Jacobi in the lead are riveting, and the Hollow Crown version showcases how rich the play's characters are. Richard III has the disadvantage of coming into this competition with bad baggage: Derek Jacobi's cartoonish Richard in London's West End production in 1989, Kevin Spacey's überhamming as Richard in a hackneyed interpretation by Sam Mendes with the Bridge Project in 2012, and Folger's burial-obsessed interpretation in 2014. But go to the bench, and you will find Ethan Sinnott's Deaf Richard at NextStop Theatre in 2014, the Drilling Company's modern Shakespeare in the Parking Lot ensemble giving an all-cylinders, first-to-last-act performance, and WSC Avant Bard's sometime-in-the-future production. With such depth behind the three Top 20 Shakespeareances performances of Benjamin Curns (ASC 2012), Antony Sher (RSC 1985), and Ian McKellen (National Theatre tour, 1992), Richard III grinds its way past the later play of an earlier Richard and into the Elite Eight.

Tom Hiddleston plays Henry V, seen here after the Battle of Agincourt, in the Henry V installment of the PBS series The Hollow Crown. Photo by Nick Briggs, Neal Street Productions.

2. Henry V (9) vs. 3. Henry IV, Part One (9)—Describe each play in one 30-word sentence to someone unfamiliar with Shakespeare. Henry IV, Part One: A partying prince, who hangs with thieves and the fat, funny Falstaff, proves his worthiness to his father by fighting a hotheaded rebel, and there's this weird Welsh guy, too. Henry V: An English King, after hearing a treatise on Salic Law, invades France, wins a big battle against incredible odds, courts a cute princess, and there's this annoying Welsh guy, too. Henry IV wins, easy! Yet Henry V is the one that gets more play—even despite IV featuring the most famous comic character of all time in Falstaff. We might see why in this round's head-to-head match between Henry V and his younger self. Instead of merely playing Shakespeare's text, many directors and actors try to interpret him. That's a problem for Henry IV, Part One, as evidenced by the many less-than-satisfactory productions I've seen. It is simply a good yarn with great characters and wonderful lines, comic and emotional: If you simply tell the story, it's a great play (ASC 2009 and 2013). Conceptualize it, and you eventually hit dead ends (STC 2014, RSC 2014, WSC Avant Bard 2011). Henry V opens with Chorus telling us to use our imaginations to fill out the tale about to be presented, and there's more room to present the king and other characters in various shades: It's a pro-war play, it's an anti-war play, it's a neutral-about-war play. Henry is a master politician (Oregon Shakespeare Festival 2012), Henry is a man of strict morality (Folger 2013), Henry is just a guy who inherited the throne and determines to do the best he can (Hollow Crown). And if you simply want to tell the Henry V story that Shakespeare gives us (ASC 2011), it's a great play, too. I'm a big fan of Henry IV, Part One, but based on the stage and film record, Henry V is the Hal that moves on to a showdown with Richard III for the History Genre crown.

Polonius Genre

Shylock (James Keegan) and Antonio (René Thornton Jr.). in The Merchant of Venice at the Blackfriars Playhouse. Photo by Lauren D. Rogers, American Shakespeare Center.

1. The Merchant of Venice (12) vs. 4. The Winter's Tale (9)—It is a play that gives so many theater practitioners fits, one that, because of the Baby Boomer culture's mindset, seems almost impossible to stage. I'm talking of The Winter's Tale, of course. It's not the “whoa! Really?” plot twist at the end that trips us up but the hot-and-cold plot itself that confuses an audience accustomed to having its performance art assigned to clearly labeled bins. Most productions I've seen divide the play's tone into two parts: tragedy in the first half, comedy in the second. Even then, the happy ending is infused with sorrow (never so much as with the Pearl Theatre Company production this year). However, Shakespeare didn't write the play with such a clear demarcation, as there are comic and tragic bits aplenty on both sides of the intermission. The Winter's Tale is a roller coaster of a play, and like a roller coaster, you can't drive it; just raise your hands and let nature do its thing. When you do, you get the masterpiece productions that were the ASC's 2012 offering and Peter Hall's End Games Festival version at the National Theatre in 1988. The Merchant of Venice scares modern theater, too, but that's due to its blatant anti-Semitism and racism. What was comical in Shakespeare's time has become more historical tragical in our post-Holocaust and post-Civil Rights society. Directors respond by playing up the tragedy of Shylock (some have even cut the fifth act altogether) and setting the play in an obviously racist timeframe (early 20th century in Public's 2011 Broadway hit and STC's bloated production the same year), including, insightfully, the future (Theatre for a New Audience, 2011). This ends up wallpapering Shakespeare's purpose. In painting what was, in his time, the stock comic Jewish villain, Shakespeare added some broad strokes of humanity. He also added dashes of distasteful color to his romantic couple and their rich Christian friends at the play's center. When you let go the harness and let the play's nature take its course, as Maryland Shakespeare Festival and ASC did in 2012 productions, you end up with a thrilling but deeply resonating drama and clever comedy. I've seen that happen more with Merchant than with Winter's Tale, but what ultimately sets these two plays apart is Shylock, who inspires so many great performances, and it is on his back that The Merchant of Venice moves on to the Elite Eight.

6. Cymbeline (6) vs. 7. Timon of Athens (4)—Timon is one of the tournament's two play-in plays to reach the Sweet 16 (the other is The Tempest in the Comedy bracket), and it has done so largely on the outsized performance of the ASC's Actors' Renaissance Season production last year, though the Public's 2011 rendition also scores plenty of points. Cymbeline rode into the Sweet 16 on the strength of 2014 MVP play from Fiasco Theater at the Folger and solid play from ASC in 2012 and the STC in 2011. It's a tight contest between two of Shakespeare's most obscure titles—and, perhaps, two of his most despised plays among Shakespeare fans (for the record, I've always liked Cymbeline; Timon not so much)—so let's look at Shakespearean depth. On the Timon side is one of our favorite Shakespeareances at the start of the Michael Bogdanov–directed production At the Chicago Shakespeare Theater in 1997. Selected members of the audience (including Sarah and me) were invited onto the stage for Timon's party. We drank champagne (actually ginger ale), had our photos taken by paparazzi, hobbed with the knobs of Athens, and were personally greeted by Timon upon his arrival. So cool, but not really part of Shakespeare's text. For Cymbeline, there is the Peter Hall–helmed production that was part of the National Theatre's End Games Festival in 1988. I had to drive back and forth from my home in East Anglia and get up extra early in the morning in order to see in one weekend all three plays—The Winter's Tale and The Tempest being the other two. Cymbeline was the true highlight of the trio, and with Hall directing, it was pure textual Shakespeare. But the story doesn't end there: I was so tired heading home at the end of the festival I nearly rolled my car. Was the End Games worth dying for? Maybe not, but the performances certainly were worth the effort, and so it is Cymbeline that outlasts Timon and heads for the Polonius Genre final showdown with The Merchant of Venice.

Eric Minton

March 26, 2015

The Brackets

Click on the tournament brackets below to download a PDF version. The play titles on the PDF version are linked to their individual "Productions Seen" page on Shakespeareances.com.

For a tournament overview, click here

For the tournament play-in matches, click here

For results of the First Round matches, click here

For results of the Elite Eight matches, click here

For results of the Final Four matches, click here

For the result of the title match, click here

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances