The Worst is Never the Worst until the Worst

Finding Comfort in Edgar in Times of Woes

It was late on a Saturday afternoon two weeks ago. I was feeling a bit ill. The headache seemed like a sinus infection with pressure at the front of the skull. Having no other cold-like symptoms, maybe I had a tension headache (understandable—or, at least, prophetic). Anyway, my brain kept misfiring, making writing and accounting pretty much impossible. But not driving (right!). We were running errands, and, despite my condition, I had to drive because my wife, Sarah, is still experiencing seizures and cognitive impairment so by law she's not allowed to drive.

As I was pulling into a parking garage space, I angled too close to one of the concrete pillars. Sarah, in the passenger seat, and I both said almost simultaneously, “That was close,” upon which we heard the stomach-churning sound of concrete tugging at whatever automobile back fenders are made of these days. We checked the damage and, yep, I would need to call our auto insurance company. There's another expense on a mounting stack of bills. We finished our shopping, got home, I made dinner, didn't burn down the house. Still, I knew I needed to get some sleep—I haven't been sleeping well lately—so I went on up to bed before Sarah did.

Thus it was that, without my monitoring her, she forgot to take her medications before she came to bed.

“And worse I may be yet: the worst is not so long as we can say, ‘This is the worst.'” This line by Edgar in William Shakespeare's King Lear has been running through my head like a tape loop the past 14 days since my too-close-encounter with that pillar. The deejays of fate (in mythology, the Fates were spinners, you know) would frequently drop into the loop a bit of Gertrude from Hamlet, too: “One woe doth tread upon another's heel, so fast they'll follow.”

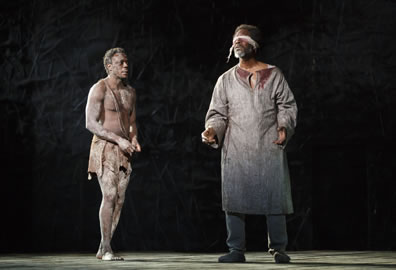

Edgar (Chuckwudi Iwuji, left) encounters his blinded father Gloucester (Clarke Peters) in the Public Theater's Free Shakespeare in the Park 2014 production of William Shakespeare's King Lear at Delacorte Theater in New York's Central Park. Photo by Joan Marcus, Public Theater.

Perspective is everything, of course. Edgar had been wrongly framed for conspiring to murder his father, driven from his home, a bounty placed on his head, and, to survive, disguised himself as a mentally ill beggar, Poor Tom of Bedlam, to hide in plain sight from society, living on, by his account, pond scum. He has it pretty bad, but he finds solace in knowing things can't get much worse for him. “The lowest and most dejected thing of fortune, stands still in esperance, lives not in fear: The lamentable change is from the best; The worst returns to laughter. Welcome, then, thou unsubstantial air that I embrace! The wretch that thou hast blown unto the worst owes nothing to thy blasts.” Then his state does get worse: He encounters his blinded father, whose eyes have been gouged out. His father calls on Poor Tom to lead him to Dover, whereopon Edgar speaks my tape loop: “And worse I may be yet: the worst is not so long as we can say, ‘This is the worst.'”

I'm not quite at Edgar's state. Yet. But the woes treading one upon the other are becoming increasingly concerning.

It started innocently enough the Sunday morning after my run-in with the pillar when Sarah had one of her intellectual seizures (a condition that strikes her left lobe, shutting down the brain's cognitive and memory functions). To use the phrase innocently enough indicates how much her neurological condition, which crashed into her head and our lives last March, has become part of our normal existence, not just the seizures but her cognitive struggles and hampered memory (which began showing up a couple of years ago). By July Sarah was no longer able to work in her contracting gig as a government and defense researcher and analyst (at which point two-thirds of our household income fell away). By August I had to take her on all my Shakespeare Canon Project trips because I couldn't leave her home alone. We currently are working on getting a consult with Johns Hopkins' Epilepsy Center, but that requires herding bureaucratic cats (something I'm pretty good at but, still, it's cats). Meantime, Sarah's seizures come on with frequency but irregularity.

This one on Sunday lasted nine hours, twice as long as the norm but not unusual. She finally got up, had some dinner, sat with that vague look of disinterest as I made conversation, then she went back to bed. She reported later that she got up in the middle of the night and had a case of vertigo. All I know is that she came down to the office on Monday morning, sent an email to her employer about coming to some resolution concerning her job status, complained of feeling dizzy, and went back to bed. She stayed there throughout the day, dizzy and nauseous. Meantime, I was trying to get a new battery for the car. The one installed last February while I was up in Connecticut for a Shakespeare Canon Project visit was leaking and still under warranty, but AAA was being ornery about actually switching it out.

Tuesday morning, I finally got the battery replaced, and with Sarah still woozy and nauseous, I got her in to see her primary care physician. He sent us on to the emergency room. With a bag of IV fluids, an extra dose of seizure medication, and some antinausea pills, Sarah was released to go home. She spent the rest of the evening “recovering.” Per discharge instructions, the next day I set a follow-up appointment with the neurologist for 6:15 a.m. Thursday morning—not a typo. As I arrived at the body shop for my repair estimate (based on the estimate, rear fenders apparently are made of uranium), the neurologists' office called asking if we could switch to 2 p.m. on Friday to fill a canceled spot: The neurologist wanted to spend more time with us than the 15-minute Thursday morning appointment would allow.

Just as well; Sarah was back in the emergency room Thursday morning, her condition worsening. In fact, her behavior—unable to even sit up—resembled my father right after his stroke. That she passed the stroke tests didn't reduce my concern born in an abyss of knowledge. A few hours later, she was back home having been dosed with stronger antinausea medicine. Best guess by the doctors and my own experience is that she's had a bad case of vertigo throughout the week that may have been kicked off by Sunday's seizure or some virus—perhaps what I had the previous Saturday. She was better Friday, and her neurologist displayed much more urgency on getting her into Johns Hopkins, starting with getting her an MRI. We tried to get an MRI last spring, but the effort stalled because of special protocols involving Sarah's pacemaker. Though the neurologist ended up dismissing the need for an MRI then, I got all the documents lined up, so now we just need to get the appointment set.

On to the funeral Saturday in Asheville, North Carolina. This was for my aunt, and I knew how important it was to my uncle for us to be there. The 6 1/2-hour drive was one thing, but I was dealing with issues on two fronts: Sarah's condition and a literal front, a winter storm due to arrive in Asheville at the same time we were for the 3 p.m. funeral. Blizzard conditions were forecasted through Monday morning. We needed to get home Sunday. Heading back north would get us trapped in the mountains, so after studying the weather patterns and forecasts, I determined that if we left right after the ceremony, we could head east, outrace the system, and spend the night in Raleigh, North Carolina, on the edge of the farthest distance the storm was expected to reach by Sunday morning. Then we could head back north through Richmond, Virginia, bypassing the worst of the conditions.

The storm, however, defied forecasts, going farther east and north. We woke up Sunday morning to some six inches of snow with ice underneath, and Richmond was forecasted to get major snowfall by midmorning. We had to extend our hotel stay for a night. We were prepared: we had packed extra underwear, and I took my traveling office with me so I could continue working on Shakespeareances.com matter and the draft for the Shakespeare Canon Project's book, Where There's a Will: Shakespeareances Through the American Way (I've fallen way behind schedule on that project the past week). We endured the power outages at the hotel without too much hassle, but then the storm did something I've never seen before: it circled and came back through Raleigh. We had to wait out more snowfall Monday morning and then leave just after noon to make it home during a five-hour window when the temperatures were hovering above freezing.

Tuesday, we woke to no hot water. Our hot water heater is on the brink of extinction. The plumber did a temporary fix, but we need a new one—soon. At least Sarah has not been totally incapacitated since her last trip to the emergency room—just partially. She had an apparent seizure on Saturday as we were driving to Asheville; and on Sunday in Raleigh; on Monday in Raleigh and continuing as we started the drive home; on Tuesday; on Wednesday; on Thursday; on Friday; and then today, she had another one. Her seizures have reached a new frequency: eight days a week.

This impressive parade of woes with 76 trombones leading have been knocking me every which way but up, but I have to admire its epic Shakespearean proportions. On top of managing all of these crises, and managing Sarah, and managing the medical bureaucracy, and hoping I can manage to find time to write (I'm writing this on a Metro train and while waiting for an appointment), I'm also trying to manage our budget. We're nowhere near destitute, and we've got near perfect credit (no hyperbole, that: our scores are 850, 850, and 849), but we will have no Christmas gifts, I'm shopping for groceries using a budget system I used when I was unemployed after college, and I'm soliciting as many freelance writing and editing gigs as I can, even with the other pressing deadlines I have.

The sequence of woes Gertrude refers to traces back to a single incident, one man's decision to kill his brother. Without that moment, Gertrude wouldn't have been widowed and wouldn't have married Claudius, which wouldn't have ticked off Hamlet, and the murder victim himself wouldn't have been ticked off, which wouldn't have led to Hamlet sometimes feigning madness, which wouldn't have inspired Polonius to plant himself as a spy in Gertrude's bedchamber, which wouldn't have gotten himself stabbed when Hamlet mistook him for Claudius, which wouldn't have led to Ophelia going mad and killing herself, and on down the chain to the catastrophic destruction of Denmark's government. I'm not suggesting there's an evil deed at the root of all our woes, but there is a simple causal factor: Sarah's neurological condition (and whatever might have caused it). Otherwise, she would have been driving that Saturday night, and she wouldn't have had any seizure medication to forget taking.

Does that, however, take into account the car battery, the funeral, the winter storm, or the hot water heater? I'm feeling like a fly to wanton boys, a sport for the gods. Yet, a Murphy's Law truism for military spouses decrees that when the service member deploys, everything goes wrong back home: The car dies, the washing machine breaks, one kid breaks an arm, the other gets the mumps, the HVAC sputters as the temperature drops to minus 24. Some of this is happenstance, but one military family expert told me that stress is infectious and may affect the appliances and other mechanical matter around the house. This is not as metaphysical as it sounds, for I've experienced the increasing impact of stress on my minute-to-minute behavior, perhaps being a bit too aggressive turning the dial on the washing machine, leaving the hot water on longer than necessary, misjudging my angle into the parking space.

I'm not buying Romeo's contention to Juliet that "all these woes shall serve for sweet discourses in our time to come" (especially given that Romeo and Juliet didn't have time to come). Instead, I'm finding solace and inspiration in Edgar. For all the nihilism that King Lear represents, Edgar survives. It's not easy, it's not pretty, but at the point he whines about his situation and it gets worse, he realizes that “the worst” is something incomprehensible, whether psychological or anatomical (i.e., death). So he turns all his attention on relieving his dad of his despair. At play's end, amid all the dead and about to die on and off stage, Edgar and Albany are left alone. Edgar speaks the play's last lines in the First Folio edition (Albany speaks the final quatrain in the 1608 Quarto version).

The weight of this sad time we must obey;

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest hath borne most: we that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long.

There's a moral in there, of course, one that strikes home for me, obeying the weight of this sad time for Sarah and speaking what I feel—to her, to the doctors, to you—whether I ought to say it or not (I ought to say it to the doctors, yet they leave the herding of medical bureaucracy cats to me). Edgar then acknowledges the tragedy that Lear, Gloucester, and the rest have suffered. However, literally between the lines—“we that are young/shall never see so much…”—are Edgar's own tragedies, experiences that he doesn't express. I'm sure Shakespeare could have inserted another couplet in there—

The oldest have borne most: we that are young—

Though cast in naked shame and eating dung,

In fated path travails a father's wrong—

Shall never see so much, nor live so long.

Edgar, however, doesn't dwell on his own woes. He carries on, for however long.

Eric Minton

December 17, 2018

Reader response:

I read this piece on Edgar and his "woe" phrase. I read the whole article—it was excellent. Well done.

Michele Dalton

November 12, 2024

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances